Southern NM pantry aims to fight hunger, stigma with new building

At a glance: Through intentional design of its new, expanded facility, a Las Cruces food pantry is taking cues from a movement nationwide to dignify food assistance services — and people’s experiences of them. Journalist Damien Willis explores in this solutions-based story what this means for pantry clients and food insecurity in the New Mexico’s second-largest city.

Volunteers with Casa de Peregrinos, or “House of Pilgrims,” food pantry wrangle shopping carts on Monday, Aug. 21, 2023 at the newly opened building on West Amador Avenue in Las Cruces, New Mexico. The facility is expected to boost the organization’s capacity to serve residents in need. (Photo by Diana Alba Soular/SNMJC)

LAS CRUCES - As one pulls into the parking lot of Casa de Peregrinos Emergency Food Program’s new warehouse and distribution center at 999 W. Amador, Bldg. 1, you could easily believe you were arriving at a nice grocery store. Though the new facility, which began service Monday, Aug. 21, is actually a remodeled feed store, the new facade is as welcoming as a supermarket — and that’s very intentional.

As the need for emergency food assistance rises in Doña Ana County for various reasons, Casa de Peregrinos is working to expand its reach and is removing some of the barriers that lead to a stigma around food insecurity. It’s an approach that’s been tried to varying degrees in other cities, and some have seen success.

Greater capacity to meet growing need

The new 13,000-square-foot facility, located at the entrance to the Community of Hope campus, is nearly three times larger than Casa de Peregrinos’ previous warehouse and distribution site. Executive Director Lorenzo Alba Jr. said the greater capacity will allow the nonprofit organization to serve more Doña Ana County residents, and the facility’s design will provide a more streamlined experience for clients.

“I keep reminding my staff that space is our friend now,” Alba said. “All these things that we weren’t able to do, we’re able to do them now. All these things that we might have put off before, now we have the space to do the work and we need to make the best of it.”

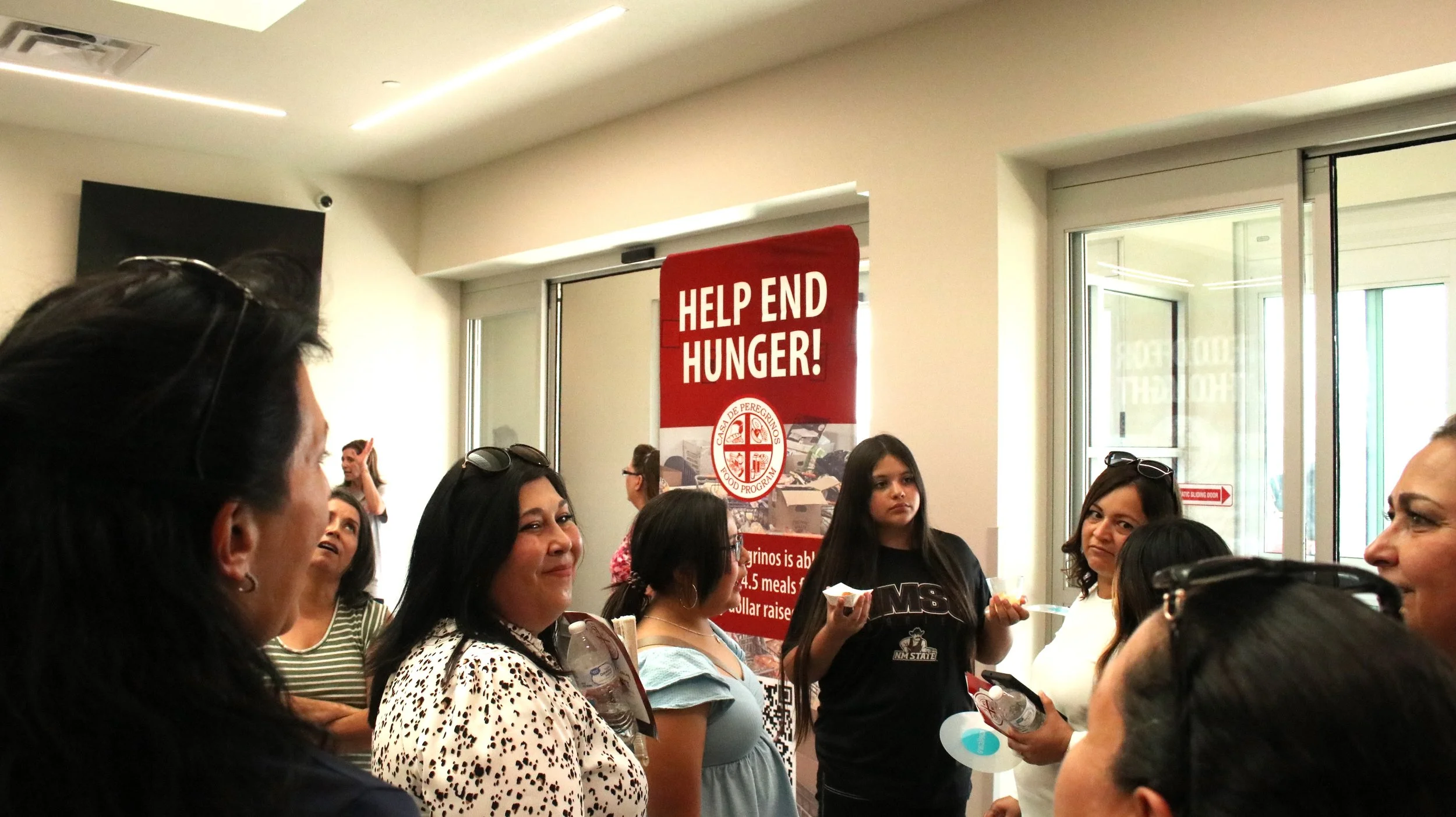

The nonprofit inaugurated the new building with a ceremony Aug. 11, drawing several hundred attendees. Funding for the project included $3.83 million in state legislative appropriations, $3.75 million from the City of Las Cruces Telshor Fund and $168,458 in state capital projects funds. In addition to the building overhaul, the project also included the construction of a new road to the west of the facility and a master plan for the surrounding Community of Hope campus. The road, Alba said, will make the campus safer and more accessible in the event of an emergency.

A crowd of several hundred attendees gathered for a ribbon-cutting ceremony Friday, Aug. 11, 2023 in front of the newly renovated building that’s home to Casa de Peregrinos food pantry in Las Cruces, New Mexico. (Photo by Diana Alba Soular/ SNMJC)

Casa de Peregrinos, by far the city’s largest food distribution effort, currently serves about 35,000 Doña Ana County residents each year. That’s just over 50 percent of those in need, which the organization estimates to be around 60,000. The organization partners with 15-20 external agencies in an effort to expand its distribution.

As of 2021, one in seven (or 13.8 percent) Doña Ana County residents were food insecure, according to Feeding America, the largest hunger-relief organization in the United States. However, one in five children in Doña Ana County (19.9 percent) suffer from food insecurity. The organization says Doña Ana County is lacking 5,303,800 meals per year.

Jonathan Ledbetter, 44, a military veteran, was among those visiting the food bank on its first day of operations Monday. He and his partner moved to Las Cruces from the Southeast U.S. about 14 months ago after he lost his job as a tattoo artist. The couple lived at first in a tent and then in a small camp trailer on public lands, moving every couple weeks to a new spot due to BLM regulations. They struggled to find a rental in part because they own a Great Dane, and couldn’t find a place that would accept pets. They recently moved into housing with the help of the V.A. – timely because their son was born about three weeks ago. The help with food, he said, has been valuable to his family over the past year or so.

“This place is awesome,” he said of the new facility. “The people are friendly. They’ve got AC. You’re not having to stand outside. That’s a major plus, too.”

That’s in contrast to the nearby, former pantry that was cramped, showing its age through wear, and didn’t have a sizable lobby, which meant clients had to wait outside in a line for their turn to be served. Often Casa de Peregrinos clients mingled on the outdoor patio with homeless clients of the adjacent Mesilla Valley Community of Hope offices, who would at times obstruct the sidewalk.

Several clients and volunteers of Casa de Peregrinos food pantry say a new facility at 999 W. Amador Ave., Bldg. 1, in Las Cruces will be an upgrade from the cramped former facility, located just to the south. Volunteer Olga Robles helps load groceries into a cart in the former building on Monday, July 31, 2023. (By Diana Alba Soular/ SNMJC)

Causes behind the growing need

In recent months, food banks and food pantries have seen a growing demand for their services, according to organizations committed to addressing hunger.

“We’ve been seeing the numbers climb a little bit,” Alba said, adding that he believes the cost of food due to inflation is playing a significant role in the increase. He said Casa de Peregrinos has seen its food prices increase by 21 percent.

“I’m going to be serving on a few panels with Sen. Ben Ray Luján and a couple of other folks here in New Mexico to really push for a robust Farm Bill because that’s where we really need to be focusing. This is one of those years that the farm bill gets approved, and what goes on that farm bill stays there for five years.”

The Farm Bill, last reauthorized in 2018, provides emergency assistance and loans to farmers, but also supports the nation’s federal nutrition programs, including The Emergency Food Assistance Program — known as TEFAP — and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, formerly called food stamps.

TEFAP is a federal nutrition program that provides 35 percent — 12.2 million pounds — of food for the Albuquerque-based Roadrunner Food Bank to distribute in all 33 New Mexico counties, which provides much of the food for Casa de Peregrinos.

Another reason some Doña Ana County residents are feeling the pinch is the end of the federal SNAP emergency allotments, which ended in March. Initiated in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, these allotments provided up to $750 monthly for a three-member family to spend on food. Now, with these emergency funds ending, such families only receive $335 per month, according to the New Mexico Human Services Department.

“Over and over again, we’re hearing from our partners that families have returned to their distribution sites after being away from it for some time due to — they specifically state — due to the decrease in SNAP benefits,” said Shelby Koza, a senior regional manager for Roadrunner Food Bank who is based in Las Cruces.

Addressing the stigma of food insecurity

One major barrier to addressing hunger is the stigma attached to asking for help, according to the Food Research and Action Center. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the economic stability of millions in the U.S., leading to increased reliance on government safety nets such as SNAP. While these programs — some of which were expanded through the 2020 Families First Coronavirus Response Act — helped avert a significant rise in hunger and poverty, they also spotlighted the pervasive stigma associated with receiving public assistance. This stigmatization not only impacts policy implementation but also deters eligible individuals from accessing necessary support due to fear of societal judgment and internalized shame.

“I’ve met a lot of people who have come to food distributions who are embarrassed to have to be there,” said Sonya Warwick, director of communications for Roadrunner Food Bank, a key supplier to Casa de Peregrinos.”But they’re there because they are resorting to the last available help they know to access. But yes, I’ve met many people who are also afraid to ask.”

Warwick said meeting people with “kindness and compassion” is important to help make them feel more comfortable.

“We do hear that; it still happens,” said Alba, when asked if stigma is a problem. “We’re trying to break that by adding different ways people can get food. We don’t just want to do it the traditional way. We want to do it other ways, too.”

People tour the interior of Casa de Peregrinos’ new food pantry and warehouse during a grand opening event on Friday, Aug. 11, 2023 in Las Cruces. (By Diana Alba Soular/ SNMJC)

Equity through architecture

Much thought went into the design of Casa de Peregrinos’ new facility — and it wasn’t all about food storage and distribution. The site was designed to look, from the outside, like a grocery store. It features electric, sliding doors at the entrance, as well as custom accent bricks in the facade. The signage is not dissimilar to a grocery store. A cart return aisle leads into the lobby — akin to a Walmart store, for instance.

“We’re expecting a slight increase (in clients) because I think people will get more comfortable,” Alba said.

The new city-owned facility was designed by Huitt Zollars, an award-winning architectural firm in Albuquerque. There is a relatively new conversation taking place about how to better incorporate equity in architecture. Some architects are exploring ways to bring more dignity to the trade.

“We wanted the look of it, from the street, to be inviting into the parking lot,” said Diego Santistevan, senior designer with Huitt Zollars who worked on the new pantry. “We wanted it to look somewhat modern but also still have a presence of the community here.”

Architecture and urban design play a hidden but powerful role in perpetuating racial and economic segregation, according to a study published in the Yale Law Journal. Furthermore, while legal and civil rights frameworks often focus on overt discriminatory policies, this study suggests that the law must expand its purview to consider built environments as tools of exclusion. Acknowledging the subtle ways architecture can segregate, advocates urge a rethinking of how buildings are designed and a greater push toward ensuring urban spaces are accessible and welcoming to all, irrespective of race or economic status.

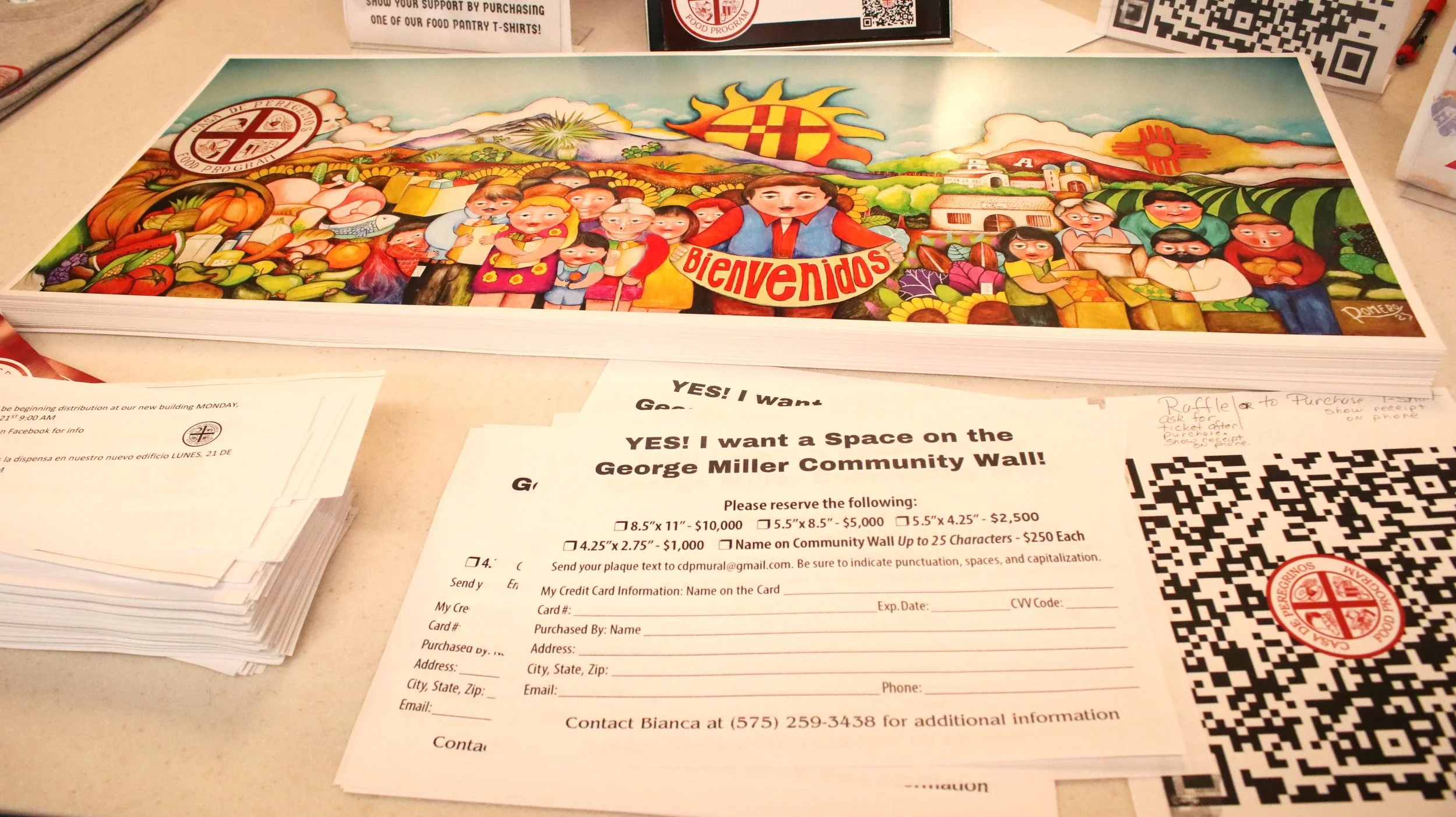

The new Casa de Peregrinos also features a commercial kitchen in the lobby, where clients can learn how to cook healthy meals. The organization has partnerships in place with New Mexico State University, Doña Ana Community College and Las Cruces Public Schools to help develop programming. Guests arriving in the lobby are greeted by a mural by local artist Francisco Romero, a well-known Las Cruces muralist. The richly colored mural was designed to capture the vibrant history, diversity and strength of the community, as well as the history of Casa de Peregrinos, Alba said.

Diego Santistevan, senior designer with Huitt Zollars who worked on the Casa de Peregrinos facility, explained how elements of the building were meant to resemble a grocery store and create a welcoming space. Santistevan was among attendees Friday, Aug. 11, 2023 at a grand opening event in Las Cruces. (By Diana Alba Soular/ SNMJC)

By incorporating fun, uplifting, community-themed artwork into the lobby, the pantry moved many degrees away from what otherwise might feel like an unassuming office space, infusing it instead with local character. Several food pantry clients, including Ledbetter, commented about how they appreciated the mural. He agreed that the building had a supermarket “feel.”

“I could see they were going for that,” he said. “If that’s what they’re trying to do, they achieved it as best as you’re going to do for a food distribution place.”

Plus, he said, the facility wasn’t as “dry and gloomy” as the previous building.

“It doesn’t feel like you’re in an institution,” he said.

Alba hopes to invite other art installations in the future, to make the space more warm and welcoming.

Another asset in the lobby is a large skylight that allows natural light to filter in, as opposed to relying upon artificial lighting only — an intentional feature meant to create a more inviting space, Santistevan said.

On the east side of the building, the new facility also features a drive-up pantry, which Alba said will increase the organization’s effectiveness. Accommodating 16 cars at a time, the shaded area allows clients to sign up online in advance, schedule a pick-up time and have their groceries prepared in advance of their pick-up. Alba said he believes this will help remove a barrier and some of the stigma associated with seeking food assistance because people won’t have to leave their cars and won’t be as noticeable.

Mariachis perform in the lobby of the new Casa de Peregrinos food pantry on Friday, Aug. 11, 2023 to mark the grand opening of the building in Las Cruces, New Mexico. (By Diana Alba Soular/ SNMJC)

Meanwhile, elsewhere

Some communities have implemented a full-blown supermarket model for food pantries, where clients go in with carts, select their food and “check out.” Some use their SNAP, WIC or EBT benefits; other sites may simply distribute the food for free, as Casa de Peregrinos does.

The emphasis is on equitable access to nutritious food. According to Food Bank News, several top-tier food banks have begun introducing innovative distribution outlets that prioritize health and convenience. For instance, Atlanta's Community Food Bank, which ranks among the nation's top ten with a 2019 revenue of $164 million, has introduced upscale market-like outlets in hospitals and a high-capacity Community Food Center that promises to distribute 650,000 pounds of healthy food in its first year. Meanwhile, Greater Boston Food Bank has successfully partnered with the local YMCA to create the Mystic Community Market, a client-choice pantry that's shown signs of success. In Houston, the city's Food Bank, which is the third-largest nationally, has embarked on an ambitious "Food Farmacy" program in collaboration with the Harris Health System, targeting patients with heightened diabetes risk and offering them balanced food options every two weeks. Alba said Casa de Peregrinos is considering a similar offering.

Feeding America partnered with Cornell University to study the effect of nudging food pantry clients while giving them choices in a grocery-market setting. Nutrition information and the appealing display of food around the store increased the likelihood that food pantry clients would choose healthier foods by 46 percent.

Though offering residents a choice of food is a growing trend nationally, Casa de Peregrinos’ new facility stops short of that. Clients can enter the lobby to pick up their bundled groceries, but the new building’s interior isn’t lined with food-laden aisles that residents can browse at their own pace and select their own items, like in an actual grocery store. Alba said, however, he hopes to be able to move in the direction eventually.

These strategic shifts focusing on building design and client experiences are representative of a broader transformation among America's leading food banks. Through collaborations with health care providers, schools, and community groups, they're striving for a more holistic approach to combating food insecurity. This new direction does more than just feed the hungry; it promises improved health outcomes, closer ties to local communities, and a robust response to the challenges of the modern era.

For instance, Redwood Empire Food Bank in Santa Rosa, California, launched its Food Connections Market. “Modeled like a mini Whole Foods, the market offers a “hyper-dignified” experience to customers who are likely to be using SNAP or WIC benefits to pay for their groceries, or who want to stretch their dollar,” according to Food Bank News.

Prints of a colorful mural that welcomes visitors in the lobby of the new Casa de Peregrinos food pantry in Las Cruces, New Mexico, were sold as a fundraiser during the facility’s ribbon-cutting on Friday, Aug. 11, 2023. (By Diana Alba Soular/ SNMJC)

In 2018, the Northern Illinois Food Bank, located in Geneva, Illinois, adopted the concept of online ordering with a focus on customer service. Through the creation of My Pantry Express, clients can now access an online grocery where they can order the food they need (for free) and pick it up at convenient locations. By the end of its first year in June 2019, My Pantry Express had received more than 20,000 orders and provided more than 826,000 meals, according to Food Bank News.

In Manchester, New Hampshire, the Families in Transition food pantry adopted the supermarket model and, as of 2022, was serving more than 1,000 families each month, according to Manchester’s WMUR.

Overall, these models are relatively new. As a result, it’s difficult to find scientific data on how effective it is at reaching a greater number of people experiencing food insecurity or reducing stigma for those being served. Given that Casa de Peregrinos’ new building is just days into its first-ever operations, it’s too soon to fully gauge the impact the facility could have on clients’ attitudes toward food assistance.

Alba said Casa de Peregrinos hopes to continue expanding Casa de Peregrinos’ reach by at least 1 or 2 percent per year. With the new facility, drive-up service and community partnerships, he believes the pieces are to do that.

Ledbetter, a food pantry client, said despite the challenges he’s gone through, he’s felt welcomed by Las Cruces since moving here more than a year ago. He said Casa de Peregrinos — and its new building — are signs the community cares.

“I just love seeing people help each other out in the community here,” he said. “It feels really good to be back out West.”

Damien Willis is a journalist based in Las Cruces who’s working with the Southern New Mexico Journalism Collaborative to cover pandemic recovery from a solutions-reporting lens. For info, visit www.southNMnews.org or surNMnoticias.org. Diana Alba Soular, SNMJC project editor, contributed to this report.

Lorenzo Alba Jr., executive director for Casa de Peregrinos, slices inaugural ribbons celebrating the completion of a newly renovated city-owned building that will serve as the Las Cruces nonprofit’s warehouse and distribution center. The new facility replaces an aging, too-small building located just to the south. (By Diana Alba Soular/ SNMJC)